|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Easter

|

|

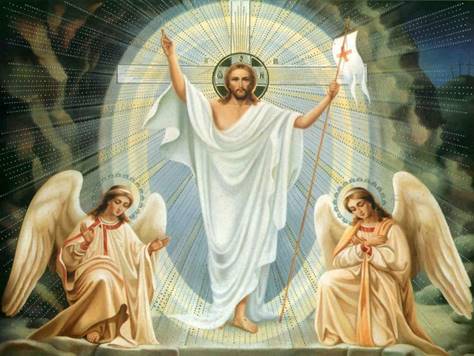

Easter is the most holy

season of the Christian year and marks the death and resurrection of Jesus.

As such, the central message of the Christian faith is played out during this

time. This message is that Christ has power to defeat death and that eternal

life is a freely given gift of God. As Christians, we die in Christ and we

are reborn in Christ. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Moving a little deeper

into the theology, Christ is portrayed as the sacrificial lamb that took the

sins of the entire tribe to let them start afresh in the new year. This

sacrificial lamb was eaten as part of a ritual meal, which originally

commemorated the ‘first fruits’ of the new agricultural year. In Exodus, we

read that the Israelites were instructed to mark the doors of their houses

with the blood of a sacrificial spring lamb to avoid being killed as the

‘Angel of Death’ passed over. Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross fulfilled the requirements

of all previous ‘blood offerings’ and so such sacrifices do not form part of

the Christian religion. But the association of his ‘once-given for all-time’

sacrifice with the Passover (Pesach in Hebrew) has led to the season being

given this name, usually as some derivation of the Latin word Pascha. Christ

as the sacrificial or Paschal lamb remains a powerful part of Christian

imagery. But, as with Christmas,

Easter has roots that lie way back in our culture. Bede tells us that the

ancient Anglo Saxons worshipped a goddess called Eostre.

As with her continental ‘sister’, Ostara, Eostre

evokes a sense of the ‘east’, the direction from which the sun rises and the

new day dawns. Eostre’s season was roughly April

and was strongly associated with spring time and the on-set of the new

agricultural year. Eostre was the time of renewal

and rebirth as well as being strongly associated with fertility, not least

the start of the lambing season.

It is easy to see how this

was absorbed into the Christian calendar. Many of the older North European

traditions were absorbed with it, including the imagery of eggs and rabbits as

symbols of fertility and new life. Eostre is not an

Angel of death, but an Angel of life. She brings forth the sun and the warmth

of spring. It is no wonder that she remains a most powerful symbol of Easter

– one that in many ways has proven more powerful than even Christ on the

Cross. This should not worry us for she is also a powerful symbol of the

central message of Christianity as it speaks to us – Christ is Risen! Our folk Easter therefore focuses not on the death

of Jesus as do some traditions, but on His Rebirth. The resurrection is also

transformative in that it offers us a new life in the sense of a fresh start

and a different way of seeing things through the eyes of Christ.

Moreover, and unlike

Christmas, the imagery of our ‘folk’ Easter with its emphasis on rebirth and

renewal has remained more separate to the formal religious events of the

period. In other words, there is a greater difference between your experience of Easter if you attend the various religious

ceremonies of the Church than if you do not. The Easter Bunny is also a

folkloric symbol of Easter, depicted as a rabbit bringing Easter eggs.

Originating among German Lutherans, it was originally seen as a judge,

evaluating whether children were good or disobedient in behaviour. In legend, the creature carries colored eggs in his

basket, sweets and sometimes also toys to the homes of children. In this, the

Easter bunny is a bit like an Easter version of Santa Claus.

This kicks off ‘Holy Week’

which is a liturgical preparation for the key events known as the ‘Passion’ –

which is derived from Pascha and means sacrifice. Most people do not engage

much, if at all, with the services of Holy Week as our focus is on the joy of

Easter day itself. But it is important to have an understanding of the events

that lead up to this joy, especially if we are to

understand the significance of the light defeating the darkness. ·

Holy Monday is associated with biblical stories of ‘the

cursing of the fig tree’ which withers because it has not sufficiently

brought forth the fruits of repentance, the ‘questioning of Jesus’ authority

by the Temple Priests and the expulsion of money changers from the Temple.

·

Holy Tuesday foretells the betrayal of Jesus by Judas

Iscariot during the ‘Last Supper’.

·

Holy Wednesday focuses on the anointing of Jesus with

expensive oils and the plot by Judas to betray Him and to deliver Him to the

Jewish authorities. A Chrism service may be celebrated on this day in which

holy oils are blessed for treating the sick. Holy Wednesday is often

completed within the Anglican tradition by a celebration of ‘Tenebrae’ which

is a series of readings and responses as the candles in Church are gradually

extinguished in preparation for the darkness of Christ’s death.

·

Maundy Thursday commemorates the last Supper of Christ

and may be celebrated with a Eucharist service after which the Church bells

are rung. Altars are stripped of their cloths and crucifixes are removed or

covered. The origin of the term ‘Maundy’ is not known for certain. Many

scholars believe it is derived from the Latin ‘mandatum’,

meaning ‘obligation’ and relating to the commandment to love one another as

Christ has loved us. As a sign this, it has become associated with the

practice of foot washing following in the practice of Christ at the Last

Supper. An alternative is that it is derived from the Maundy baskets, or

purses, of money that the king of England distributed to the poor on this

day. This custom is still practiced by the monarch. Both may be right!

Good Friday commemorates the crucifixion and death of Jesus

on the Cross. In England, as in much of the Anglo-sphere, it is a public

holiday. The Book of Common Prayer does not include a specific form of

service for Good Friday, but custom has developed a three hour service, known

as the ‘Seven Last Words from the Cross’, which includes readings outlining

the passion story. More recently, the ‘Stations of the Cross’ have been

re-introduced especially into High Church services.

Hot Cross buns are typically eaten on Good Friday, though

they are as likely to be eaten on any day around this period. These are

spiced, sweet buns, made with currents or sultanas and have a pastry cross on

their top. They are cut in half, toasted and eaten with just butter. It is

also traditional to eat fish on a Friday and especially on Good Friday. Fish

pie is still popular as are dishes such as Halibut or Turbot.

Holy (or Easter) Saturday commemorates the day that Jesus’

body lay in the tomb and the ‘Harrowing of Hell’. There is no formal liturgy for

the day, but readings are often said commemorating the burial of Jesus. At

nightfall (or around 6.00pm) the Easter Vigil begins and continues through

the night until dawn.

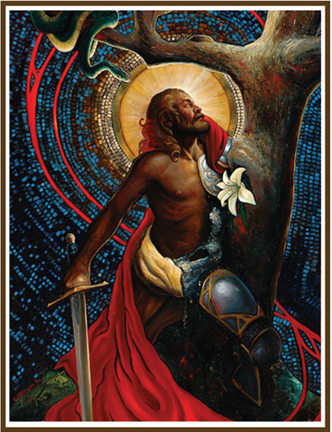

On Holy Saturday, we are also encouraged to meditate upon

the ‘Harrowing of Hell’. This ‘Anglo Saxon’ term refers to the triumphant

descent of Christ into hell, as His earthly body lies in the tomb, and His

bringing the souls of the righteous dead back out of Hell with Him. This

story is referred to in two Anglo Saxon era poems (Cædmon

and Cynewulf) as well as in Aelfric's homilies. So it was clearly an

important part of the faith for our ancestors.

Easter Sunday marks the

resurrection of Jesus and the promise of eternal life of all those who follow

Him. This is the one Sunday practicing Anglicans are expected to observe.

Even though most do not attend Church even on Easter Sunday, numbers are

usually significantly higher than usual. There are several joyful Easter

hymns which are sung, one of the most common being ‘Jesus Christ is Risen

Today’. Although not common these days, hard boiled eggs are still

decorated (usually on Holy Saturday) and exchanged on Easter Sunday. Rolling

these eggs down steep slopes as a race remains popular in many parts of rural

England.

More common, are chocolate eggs, often with sweets inside

them. Traditionally, these are hidden around the garden by parents and the

children then ‘hunt’ the eggs on Easter morning.

In some parts of England, mainly in the south-west, lightly

spiced Easter biscuits with currents in them are exchanged.

Another traditional food item eaten over Easter is the ‘Simnel cake’. The word Simnel

is thought to be derived from Latin word ‘Simila’

meaning finely ground and they may originally have been a

bread. Traditionally they were baked in the middle of Lent for what is

known as ‘Refreshment’ or ‘Simnel’ Sunday – and is

now better known as Mothering Sunday. Simnel cakes

are a bit like a lighter version of Christmas cake and seem to be enjoying a

comeback over recent years. Traditionally, they are decorated with eleven

marzipan balls representing the eleven apostles, excluding Judas Iscariot who

betrayed Christ. However, you do often see them with twelve marzipan balls,

representing Jesus and the eleven apostles.

And the traditional main meal is roast lamb, symbolising

Jesus as the lamb of God who takes away our sins through His sacrifice on the

cross.

The word ‘Pace’ is derived from Pascha, literally meaning

Easter. So these are local ‘Easter’ plays. But they are not Passion plays as

such, and only have a fairly basic link to the Easter story. In fact, they

are more in the mould of a Pantomime, pitching the hero, often St George,

against the Villain, often the Black Prince or the Bold Slasher. As St George

smites all challengers, the fool (known as ‘Toss Pott’ – a term still used

for a person acting foolishly) rejoices at George’s victories. However,

George is eventually killed (all cry ‘boo’) but then brought back to life

again by a quack doctor (all cry ‘hurrah’). Morris Men and Women come out of hibernation around Easter tide.

In fact, they will have been practicing hard during the winter months and now

keen to dance in public.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||