|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Major Feasts In

The Anglican Tradition Major

Feast days are not only important religious events marking our journey

through the Christian year, they are also important social events in which the

spiritual and secular worlds come together. Feast days remain vital parts of

our culture that are part and parcel of our identity. Advent

Advent

marks the beginning of the Church’s new year and is celebrated in November on

the fourth Sunday before Christmas and the Sunday before St Andrew’s Day. It

is a time of preparation for Christmas in much the way Lent is for Easter.

Advent traditions include keeping an Advent calendar, lighting an Advent

wreath, praying an Advent daily devotional, setting up Christmas decorations

and the ‘hanging of the greens’ ceremony. Advent

services now also include the relatively modern tradition of ‘Christingle’

which is a service dedicated to and for children. It includes using an orange

to represent the world, a candle to represent Christ as the light of the

world, a red ribbon to represent the blood of Christ, aluminium foil to

represent the nails used to crucify Him and dried fruits to represent the

fruits of the earth. Christingle services are also held over the Christmas

period and sometimes during Epiphany. Whilst ASA is generally wary of modern

innovations within the Church, it considers Christingle to be a positive

innovation, especially one that celebrates, and is a celebration for, our children. St Lucy’s Day (21st

December)

Saint

Lucy was a 3rd century martyr who, according to legend, brought

food and aid to Christians hiding in the catacombs during the persecutions of

Diocletian. She used a candle-lit wreath to light her way and leave her hands

free to carry as much food as possible. Although now usually celebrated on

the 13th December, her feast originally coincided with the Winter

Solstice, the shortest day of the year before calendar reforms. As such, it

is a festival of light and falling within the Advent season, it can be seen

as heralding the arrival of Christmastide, pointing to the arrival of the

Light of Christ on Christmas day. The

day includes processions of people holding candles to honour her work and to

represent the power of light over the darkness and anticipating the coming of

Christ as the light of the world. These

days, St Lucy’s day is mostly celebrated in Scandinavian countries and not

well known in England. However, it was an important feast day in England

right up to Puritan times, marking the start of the Yule season and the New

Year. We therefore believe it should be restored to the English tradition. Christmas Eve (24th

December)

Christmas

Eve is the day we anticipate Christmas day. It is usually marked by a fairly

simple meal in the evening, carol singing and maybe by attending a Church

service such as Midnight Mass. In England we do not exchange Christmas

presents until Christmas day itself. Christmas

Day (25th December)

This

is the day we celebrate the birth of God into our world. Church services are

held, focusing on this theme and with plenty of Carols sung. It is a time for

the nuclear family to be together and keep warm and open the presents! Christmas

is our Christianised version of the old Yule season. This was a time of peace

and warmth when families got together. So we see the cultural side of

Christmas, which goes way back into the mists of time, juxtaposed with the

celebration of the birth of Christ. Both of these traditions are positive and

complement each other well which is why Christmas is so popular. However,

neither of them bears any resemblance to the modern commercialised Christmas

which is just out to make money. Boxing Day

(26th December)

This

is the traditional day for visiting the wider/extended family and is a sort of

extension of Christmas day. The meaning of the word ‘boxing’ is shrouded in

the mystery of time, but probably was when small parcels or boxes of money,

treats and food were made available to poorer people. In later medieval

times, it became more strongly associated with richer people giving such

boxes to trades people or staff as a bonus for work well done over the year.

Servants and other staff were allowed to visit their families (presumably

with their box of goodies), hence the modern custom of visiting family. Boxing

day is also known for sports, especially horse racing, fox hunting and

swimming in the freezing sea. In some areas, especially Cornwall, the day is

also marked by Mummers plays, but this does not seem to have been a

widespread custom in England generally. Typical

food can include leftovers from Christmas day and especially ham, such as

boiled ham with potatoes and parsley sauce. Today,

Boxing day is especially associated with shopping and ‘sales’. This is part

of our modern ‘consumer-led’ culture which we do not encourage or consider

wholesome. Holy Innocents (28th

December)

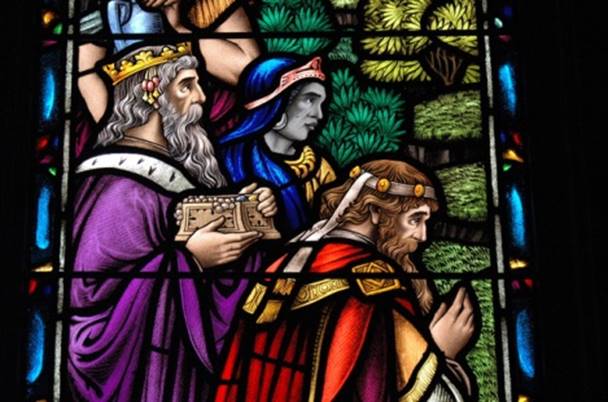

This

day marks the massacre of the holy innocents, young baby boys killed by King

Herod in his attempts to kill the Christ child. He had asked the Wise Kings to

report to him on the location of Christ when they found him, but they were

warned by an Angel that Herod intended to kill Him and so they took a

different route back to their homeland. ‘Herod’

was a title for a Jewish King appointed by the Romans to rule over the Judean

people on civil matters. This particular Herod believed that Christ would

grow up to take his place which is why he set out to kill him. When the Wise

Kings declined to let him know where to find Christ, Herod decided to kill

all male children under two years old to be sure. However, Joseph was

forewarned of this and took the baby Jesus, together with his mother Mary,

into Egypt where he remained until the death and instigation of a new Herod. The

story would have had particular poignancy with our Anglo Saxon ancestors as

it is observed during the holy period of Yule in which violence was expressly

forbidden. Naming of Jesus and New Year’s

Day (1st January)

This

day commemorates the naming of Jesus when he was circumcised, according to

Jewish custom. However, as an event it tends to get rather over shadowed by

the secular festival of New Year’s Day. Epiphany Eve or Wassailing Day

(5th January)

This marks the eve of Epiphany and the

visitation of the Three Wise Kings. At one time, Epiphany was more important

than Christmas and whilst we don’t take it that far, we do think it should be

given more prominence than it currently has. Celebrations on Epiphany eve

include candle lit processions, wassailing (either around people’s homes or

in honour of trees) and general merry making. The word ‘wassail’ is derived

from the Anglo Saxon English words ‘Wes Thu Hal’, meaning ‘Good health to

you’. Epiphany or Three Kings Day (6th

January)

This

is a celebration of the visitation of the Three Wise Kings from the east,

probably Persia, who followed a star in the sky to visit the child Jesus.

These Wise Kings were Zoroastrian Magi (or Priestly nobles descended from

Zoroaster himself). Zoroastrian priests had a reputation as experts in

astrology and these Priests had seen signs in the stars that foretold the

birth of God into our world. They brought with them gifts of Gold

(representing wealth and kingship), Frankincense (representing His priestly

status) and Myrrh (representing His anointment as the Christ and embalming

oil foreshadowing His death on the Cross). Baptism of Christ

This

day celebrates the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River by John the Baptist. It

was originally celebrated on Epiphany, but over time it became a distinct

feast in its own right. It is usually celebrated in Anglican Churches on the

first Sunday following Epiphany. Distaff Day (7th

January)

This

is a celebration of women’s work, especially weaving, and marked the return

of women to work in the evening after one final holiday celebration. It

sometimes coincided with the men’s holiday of Plough Monday and on this time

they would celebrate together and often play tricks on each other. A

distaff is a stone or rock that is used to hold unwoven fibres, usually flax

or wool, and prevented them from tangling in the spinning process. As such,

it became a symbol of women’s work in medieval Europe. ‘Distaff’ also became

a common phrase to describe the female side of the family. However,

the significance of this feast goes back deeper into our mythology. The word

‘Dis’ itself comes from the Indo European word ‘dhēi’,

meaning lady or goddesss, literally meaning to

suckle. The Disir, or Idisi,

were the Germanic and Saxon female goddesses, particularly those associated

with battle. Frigg spins the web of Wyrd (fate) from her bejewelled distaff providing an association between the Disir, the Distaff and the Three Norns

or Sisters of Wyrd. Early Saxon Christianity spent a great deal of time

reconciling their new Christian faith with their older concepts of fate,

which they called ‘Wyrd’. Plough Monday

This

is held on the First Monday after Epiphany and marks the traditional start of

the agricultural year in England and the resumption of work after the

Christmas holiday. In many parts of the country in the Middle Ages, a

decorated plough would be hauled around the villages collecting money – often

with music. This procession would be accompanied by an old woman, or boy

dressed as an old woman, called the ‘Bessy’ and with entertainment by a

‘fool’. A boiled suet pudding of sausage-meat and onions, called ‘Plough

Pudding’ and originating from Norfolk, was eaten on this day. An

old tradition associated with Plough Monday, which is slowly being restored

after having completely died out, is that of ‘Molly Dancing.’ Originally, it

would have been undertaken by plough-hands in the idle season between the end

of the Christmas period and the start of ploughing the fields in early

spring. Men would go from house to house, especially of wealthier people, and

offer to dance in return for a small sum of money. If they were refused, the

home owner was likely to find a great plough furrow through his front lawn

the next day! The men disguised themselves, sometimes by dressing up as women

and sometimes by blackening their faces. My feeling though is that everyone

knew what was expected of the ‘tradition’ and front lawns, in the main,

remained un-ploughed! Candlemas (2nd

February)

Candlemas

is a ‘Cross Quarter’ day that celebrates Christ as the ‘light of the world’

which according to John ‘shines in the darkness and the darkness could not overpower

it’. The Prophet Simeon the Righteous, declared the infant Jesus to be the

light that would illumine the nations. This image of Christ as the light of

the world has come to be celebrated in the west by the lighting of candles –

hence the term Candlemas. It is a time for lighting candles and pondering

Christ as ‘light of the world’. This

day also celebrates the ‘Presentation of Christ in the Temple’ or

‘Purification of the Virgin’ which was a ritual cleansing of a mother

following birth. This tradition was followed in olden days and known as

‘Churching’. However,

Candlemas is also a Christianised continuation of

an earlier folk tradition celebrating the beginnings of spring. The Anglo

Saxons called this ‘Ewemeolc’ and the Britons and Celts Imbolc. Ewemeolc literally means ‘Ewe’s Milk’ and celebrated the

start of the lambing season. Special feasts were held, candles and bonfires

lit to mark the decline of winter and holy wells were visited. And

so there is a theme to this feast, which like many others, goes way back into

our folk culture. This is a theme that winter is about to give way to spring

and the darkness is, and always will be, overcome by the light. Shrove Tuesday (Pancake Day)

This

is a movable feast determined by the date for Easter. To ‘shrive’ comes from the Old English word

Scrifan which means to confess. It is a time

to consider our shortcomings and wrong doings and think about how we might overcome

these in the following year. And it is a period of personal reflection that

could continue through the Lent period. But

it’s also a time to eat pancakes! Pancakes

were eaten on this day to use up rich foodstuffs such as eggs, milk and

butter. English pancakes are thin and typically eaten rolled-up with treacle,

orange or lemon juice with sugar. Ash Wednesday

This

follows Shrove Tuesday and so is also movable. It marks the first day of the

fasting period of lent, symbolising the 40 days that Christ spent in the

wilderness. Ash

Wednesday derives its name from the practice of blessing ashes from palm

branches of the previous year's Palm Sunday and using these to make the sign

of the cross on people’s foreheads. This is accompanied by the words

"Repent, and believe in the Gospel" or "Remember that you are

dust and to dust you shall return". Whilst

this practice can be a useful outward sign of repentance, we believe that a

period of inner reflection on our past actions and how we might address

things we have fallen short of is more important. And so we also call Ash

Wednesday ‘Reflection Wednesday.’ You do not need to attend a formal Church

service for this. But where these are held, an appropriate period of quiet,

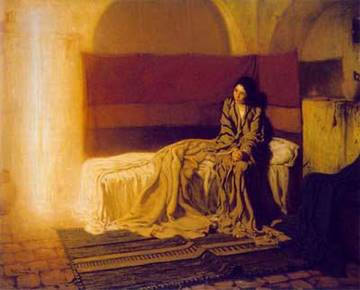

with lights dimmed, should be held for us to reflect on these things. Feast of the Annunciation or

Lady Day (25th March)

Lady

day celebrates the annunciation that Mary was to become the Mother of God. It

takes place exactly nine months from the birth of Christ on Christmas day. It

is a Quarter day, though does not fall on the vernal equinox (March 21st)

itself. It

used to be celebrated as New Years day in England until

1752, when it was replaced by January 1st following the move from the Julian

to the Gregorian calendar. As it marked the end of the old year and beginning

of the new, and because it did not fall either within or between the

ploughing and harvesting seasons, it became the traditional day on which

annual contracts were drawn up between landowners and tenant farmers. This

sometimes meant farmers changing farms and so it was not unusual for people

to be travelling from their old farm to the new one on this day. Passion Sunday (Palm Sunday or

The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem)

Called

‘Palm Sunday’ because of people placed Palms in front of Jesus as he rode

into Jerusalem on a donkey, this feast is also known as Passion Sunday

because it marks the start of Holy Week and the Passion of Christ. It is customary

on this day to be blessed by being sprinkled with holy water, followed by a

solemn procession around the Church and then back into it through the main

entrance to signify Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Holy Week Holy

Week marks the lead up to the death and resurrection of Christ. In some ways

it is a strange celebration as we have already started to celebrate the

return of the sun and warmth and now return to the death of God. But, on the

other hand, it allows us a chance for focussed meditation on the whole

‘dying/rising’ God cycle of birth, death and rebirth as well on the specific

events that led to the crucifixion prior to the celebration of Easter and the

formal beginning of the ‘light’ season. Holy Monday reflects on the

temple Priests who questioned Jesus’ authority and his ‘Cleansing of the

Temple’ by expelling the money changers.

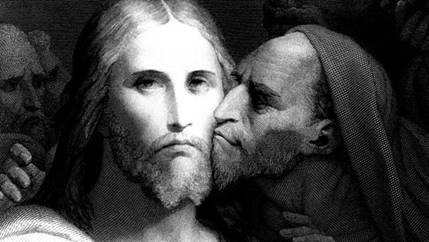

Holy

Tuesday foretells

the betrayal of Jesus by Judas Iscariot during the ‘Last Supper’.

Holy

Wednesday reflects on the

anointing of Jesus with expensive oils and the plot by Judas to betray Him

and to deliver Him to the Jewish authorities. A Chrism service may be

celebrated on this day in which holy oils are blessed for treating the sick. A

‘Tenebrae’ service may also be held, which is a series of readings and

responses as the candles in Church are gradually extinguished in preparation

for the darkness of Christ’s death.

Maundy

Thursday commemorates the

last Supper of Christ and may be celebrated with a Eucharist service after

which the Church bells are rung. The origin of the term ‘Maundy’ is probably

derived from the Maundy baskets, or purses, of money that the king of England

distributed to the poor on this day. This custom is still practiced by the

monarch.

Good Friday is

a movable feast determined by Easter. On this day we commemorate the passion

and crucifixion of Christ. However, we do not celebrate a weak Christ, meekly

succumbing to His death. We reflect the Crucifixion as told in the Anglo

Saxon poem ‘Dream of the Rood’ which tells of a strong Christ meeting His

fate head-on. It

is a day of fasting, although Hot Cross buns are eaten and traditionally the main

meal of the day is fish. We would like to develop a series of readings that

tell the story of the passion. These could be either read out in Church as

part of a formal service (including Stations of Cross if desired by a

particular congregation) or read out as part of family gatherings or meals or

simply read quietly by an individual as a personal meditation.

Holy Saturday commemorates the day that Jesus’ body

lay in the tomb and the ‘Harrowing of Hell’. There is no formal liturgy for

the day, but readings can be said, or quietly read, commemorating the burial

of Jesus. As a general rule, we do not observe the Easter Vigil. Instead,

Churches should be closed and shrouded in darkness. Any personal or family

shrines should also be covered and no candles burnt. The aim of this is to

reflect the darkness of the closed tomb.

The

Easter Vigil begins begins at sunset on Holy

Saturday and lasts until sunrise on Easter Sunday. An Easter fire is kindled outside

the Church and the Paschal candle is blessed and then lit. This Paschal

candle will be used throughout the season of Easter, remaining in the

sanctuary of the church or near the lectern, and throughout the coming year

at baptisms and funerals, reminding all that Christ is "light and

life". Once

the candle has been lit, it is carried by a deacon through the nave of the

church, itself in complete darkness, stopping three times to chant the

acclamation 'Light of Christ', to which the assembly responds 'Thanks be to

God'. As the candle proceeds through the church, the small candles held by

those present are gradually lit from the Paschal candle. As this symbolic

"Light of Christ" spreads, darkness is decreased.

Easter Sunday

Easter Sunday

marks the resurrection of Jesus and the promise of eternal life of all those

who follow Him. It is the holiest day in the Christian calendar and is a

truly joyous time as we celebrate Christ’s victory over death and his offer

of eternal life to us all. Bede tells us

that our pre-Christian ancestors worshipped a goddess called Eostre from which the modern name is derived. Eostre was a goddess of the spring, fertility and renewal

and Easter has always had a more general ‘folk’ element to it as we celebrate

the start of spring and the re-awakening of the earth.

Although

not common these days, hard boiled eggs are still decorated (usually on Holy

Saturday) and exchanged on Easter Sunday. Rolling these eggs down steep slopes

as a race remains popular in many parts of rural England. More common is the

hunt for chocolate Easter eggs. Other foods of this period include ‘Simnel Cake’ and Easter biscuits. We are also very keen

to encourage the resurgence of traditional Easter ‘Pace’ plays. St George’s Day (23rd

April)

George

is the patron Saint of England as well as several other countries. However,

not only was he not English, he only became our patron following the Norman conquest.

Consequently, the English have always been a bit ambivalent about him! We

certainly do not celebrate his feast as the Irish celebrate St Patrick’s. This

said, the old myth of George and the dragon has deep

roots in our culture. It is reflected in the story of Beowulf and in Thor

fighting giant sea monsters. So George does have roots in our culture and

something to say to us that we should delve into more deeply. We

also observe this day as a celebration of England and Englishness. We know

that English speaking people probably lived in these islands long before the

times of Hengist and Horsa

and even that Eastern England has always been part of a Germanic culture. And

so we also see this day as ‘England Day’, a celebration of our folk, our

culture and our homeland. The arrival of Hengist

and Horsa is still important as a symbol of our

beginnings and the White Horse Stone in Kent marks this. May Day (1st May)

This

marks the arrival of summer and a time when bonfires and candles are lit,

special foods eaten and ‘May bushes’ decorated. It was also the custom until

relatively recently to leave small amounts of food for the Elves and Spirits

near such bushes. Holy wells may be visited and votive offerings left for

general health and well-being and for a good summer. In

England we still have the procession of the May Queen, which may be a folk

memory from mythology of the procession of the goddess Nerthus.

Maypole dancing is also still practiced throughout the land. Ascension Day

This

is a movable feast taking place on the Thursday, forty days after Easter,

although it can be moved to the following Sunday. On this day we celebrate

the ascension of Christ into heaven. Christ becomes again the ‘Cosmic Christ’

who reigns from heaven and is still with us. In

England, it was common to ‘beat the bounds’ on this day and some parishes

continue this tradition. Oak Apple Day - or Royal Oak Day

(29th May)

This

celebrates the restoration of the English Monarchy in 1660 with the accession

of King Charles II, some eleven years after the execution of his father,

Charles I, following the English Civil War. The day was an official public

holiday in England until 1859, but is still celebrated in many quarters. Oak

Apples are not real apples and are not edible. They are odd growths on oak

trees that are often round in appearance, hence the name. The festival

commemorates the occasion after the Battle of Worcester in September 1651,

when Charles II escaped the Roundhead army by hiding in an oak tree near

Boscobel House. The day is still essentially one that celebrates not just the

Monarchy, but the English attachment to it as a part of a system that

maintains balance in Government, allows for individual freedoms and prevents

tyranny such as Cromwell’s Commonwealth. Traditional

celebrations to commemorate the event included sporting an oak apple or

sprigs of oak leaves on ones clothing and in some

areas Church doors and lych gates were decorated

with Oak beams. Smaller branches would also be placed near the door of

everyone’s house as a sign of good luck for the coming year. Some areas also

include Church processions and a blessing of the Church with an oak bough.

Many of the decorations have a ‘celebration of nature’ feel to them and may

have been incorporated into this essentially secular day to celebrate the

repeal of laws banning such folk customs by the Puritans. Whitsunday (Pentecost)

This

feast is celebrated fifty days after Easter Sunday, hence its Greek name of

Pentecost which is derived from their word for fifty. It commemorates the

descent of the Holy Spirit as tongues of fire amongst the Apostles. The

Apostles began to speak in tongues, so that every man who heard them could

understand what they were saying, irrespective of what language he spoke. In

Europe, Churches are often decorated with tree branches, usually birch.

Sometimes, large cut outs of doves are also placed in churches to signify the

Holy Spirit. In

parts of England, there are Whit walks with brass bands and with girls

dressed in white. Morris dancing and cheese rolling are also still practiced.

The origin of the term ‘whit’ is uncertain. Some believe it is a reference to

the white clothes worn by people baptised in the period from Easter Sunday.

Others think it is a reference to ‘whit’ or wisdom, to Holy Sophia which is

the Greek word for Wisdom with which the holy spirit is often associated. Trinity Sunday

This is the first Sunday following

Whitsun and celebrates God as Trinity:

Father, Son and Holy Spirit. God as Trinity is an important doctrine

within Christianity and yet has never been clearly defined, perhaps reflecting

the fact that the human mind can never fully understand the nature of God.

Nevertheless, Trinity teaches us to see God as both active within our world

and as transcendent of it. It also teaches us something of the active nature

and inter-relationship of God, this active nature being underpinned by love. Corpus Christi

Held

on the Sunday following Trinity Sunday, this is a celebration of the Holy

Eucharist, the body and blood of Christ. The service traditionally ends with

a solemn procession of the blessed sacrament within a monstrance. As it was

associated with the ‘real presence’ doctrine of Transubstantiation, this

feast day is not generally celebrated in Protestant Churches. Indeed, it was

officially banned in England in 1548. However, it has been revived in many

Anglo Catholic and High Anglican Churches, though not always with the

elaborate ritual of the Roman Rite. ASA does encourage the celebration of

this feast day – but as a day of thanksgiving for the institution of Holy

Communion as it is best known in the Anglican tradition rather than as an

affirmation of any particular doctrine of the Eucharist. St John the Baptist or Midsummer

(24th June)

This

marks the summer solstice which usually occurs around 21st June.

However, the Church celebrates it on 24th June as St John the

Baptist Day, where it is a Quarter Day. St John’s Eve is celebrated the night

before with the lighting of bonfires and candles to see in May Day itself. This

is a time for feasting and merry making, party games and celebrating life. It

is also seen as a day of magic where you might get to see the Fairy folk or

an Elf! St Joseph of Arimathea (31st

July)

Legend

tells that Joseph of Arimathea visited south western Britain on business as a

tin merchant and on at least one occasion brought his nephew, the young

Jesus, with him. Jesus spent time with the druids, teaching them and being

taught by them. Following his death on the cross, the holy family fled the

middle east and settled in this part of Britain that Joseph already knew. At

this time, Britain was independent and not under the control of the Romans.

The legend of the Holy Grael is one that has gripped the English for

centuries, despite pre-dating the establishment of England in Britain. It

represents a very important part of our mystical and religious traditions. Although

the Church of England celebrates this day on 1st August, we

celebrate it on the day before (31st of July) in common with the

Eastern Orthodox and some protestant denominations. This is mainly because we

do not wish it to clash with the important folk festival of Lammas Day. We

would also like to develop a greater symbiosis between these two days to

create something of a two-day festival. Lammas Day (1st

August)

Lammas,

or Loaf Mass, Day is the festival of the first wheat harvest of the year. On

this day, it was customary to bring to church a loaf made from the new crop

and in many parts of England tenants were bound to present freshly harvested

wheat to their landlords. In Anglo Saxon times, it was also called the ‘feast

of the first fruits’ and the new harvest would be blessed. In medieval times

the feast was known as the "Gule of

August". The meaning of Gule is no longer

known for certain. It could either mean the Yule of August, which was spelt ‘Geole’ in Anglo Saxon English, or be an Anglicisation of

the Welsh words for the 1st of August gŵyl aust, literally meaning the ‘feast of August’. Some

writers have associated Lammas with the Celtic pagan festival of Lughnasadh, named after the god Lugh who is also reputed

to have given his name to London. The

festival is celebrated with bonfires and merry making, overseen by a period

of peace – reflecting the similar practice over Yuletide. In Ireland it was

traditionally the time for handfastings which were

trial marriages lasting for a year and a day after which the couple would

decide whether to formalise the marriage or part company. Transfiguration (6th

August)

The

Gospels tell us that Jesus and three of his apostles, Peter, James and John,

climbed up a mountain to pray. On the mountain, Jesus began to shine with

bright rays of light. Then the prophets Moses and Elijah appeared next to him

and he spoke to them. Jesus is called "Son" by the father as a

voice from the heavens. The

Transfiguration is a pivotal moment in the Gospel story. The setting on the

mountain is presented as the point where human nature meets God with Jesus

himself as the connecting point, acting as a bridge between heaven and earth.

In the Transfiguration, we see Christ’s glorified body – that which

transcends death and foreshadows the resurrection. The Greeks use the word

metamorphosis which actually better explains the importance of this change. The Falling Asleep or Assumption

of the Blessed Virgin Mary (15th August)

Christian

tradition holds that the Holy Virgin underwent, as did her Son, a physical

death, but her body (like His) was afterwards raised from the dead and she

was taken up into heaven. Some western Christians believe she was resurrected

before being assumed into heaven. Most Protestants do not observe this feast,

at least in its traditional form, as there is no biblical basis for it.

Anglicans use this day to honour Mary and celebrate her entry into heaven

without necessarily believing she was physically resurrected or assumed. Holy Cross Day (14th

August)

Whereas

Good Friday observes the crucifixion of Christ, this day celebrates the cross

itself as an instrument of salvation. We are reminded of the Anglo Saxon poem

‘Dream of the Rood’ in which the cross tells the story of Christ’s

crucifixion. This

is a remarkable story of Anglo Saxon Christianity and one that should be

given great prominence by the modern Anglo Saxon Christian. It starts with

the account of a vision by someone having a dream. In this dream, or vision,

the narrator is speaking to the Cross on which Jesus was crucified. He notes

how the Cross is covered with gems and is aware of how wretched he is

compared to how glorious the Cross is. However, he comes to see that amidst

the beautiful stones, it is stained with blood. In

section two of the poem, the Cross shares its account of Jesus' death. It

begins with the enemy coming to cut the tree down and carrying it away. The

tree learns that it is not to be the bearer of a criminal, but instead Christ

crucified. The Lord and the Cross become one, and they stand together as

victors, refusing to fall, taking on insurmountable pain for the sake of

mankind. It is not just Christ, but the Cross as well that is pierced with

nails. Christ and the Cross have become one. Then, just as with Christ, the

Cross is resurrected and adorned with gold and silver. It is honoured above

all trees just as Jesus is honoured above all men. Michaelmas – feast of the

Harvest Home (29th September)

Michaelmas (pronounced ‘Mickel-mas’) is the feast

of St Michael the Archangel. It corresponds roughly to the autumn equinox

which marks the shortening of days and the beginning of autumn. It was

traditionally celebrated in England as the end of the harvest cycle and was

associated with much feasting. With the crops safely gathered, Michaelmas

marked the time for landowners to stock barns and sheds full of food, ready

for the winter ahead. Meats and fishes

were salted, to be eaten during the cold months ahead and a new accounting

and farming year officially began. Michaelmas also marked an end of many

activities which could only be carried out during the summer months, such as

fishing and fruit picking. On the day after the feast, farm labourers and

domestic servants presented themselves at a ‘mop fair’, where they could be

hired for work in the coming farming year. Many villages celebrated

Michaelmas with a harvest feast, which offered all the best of what had been

gathered and anticipated good times to come, with cupboards full for the

coming months. Michaelmas

marked the end of the agricultural year and was the time that farmers paid

off their debts, often presenting their landlords with a goose. Goose fairs

were common and some still take place. In common with the theme, the

traditional meal for the day includes a harvest goose or ‘stubble-goose’ and

a special kind of oatcake called a St Michael's bannock. Eating goose on

Michaelmas day is said to bring financial good luck for the coming year. Whilst

Michaelmas is now observed on the 29th September, it used to be on

10th October under the old Calendar. This is still sometimes referred

to as ‘Old Michaelmas’ or ‘Devil’s Spit Day’. This is because of an old

legend that the devil was kicked out of heaven on 11th October and

landed on a bramble (blackberry) bush. Each year, it is said that he takes

his revenge by spoiling brambles after this date. Some say he spits on them,

others that he pees on them! Either way, it is attested that brambles do not

taste as good after the 11th and so you should eat as many of them

as you can on Michaelmas day! Michaelmas dumplings are a traditional pudding

for this day and consist of suet dumplings with chopped apple inside them,

simmered on a bed of sweet brambles and served with cream to symbolise the

devil’s spit! Michaelmas

day was traditionally a day of reckoning, as quarter days marked the times

when rent was collected. It also marks

the beginning of the legal and school year.

St

Michael is the warrior Archangel and is honoured as the protector of the

individual against evil forces. He is also honoured as a healer. A winter

curfew came into operation in many communities from Michaelmas Day and the

church bells were sounded early in the evening from Michaelmas onwards, for

the town gates to be closed to incomers until morning. Michaelmas

is also sometimes also known as the "festival of strong will". This

reflects the association of St Michael in many Germanic countries, including

England, with Woden or Odin and sometimes also with Thor. Churches dedicated

to St Michael, especially in Germany, are often found on hills and other high

places which would originally have been sacred places dedicated to Woden. An

ancient practice, from well before the Christian era, is the corn dolly. This

was made from the last sheaf of wheat of the harvest and was woven into a

human shape, to take the place of honour on the harvest feast table. It was

believed to bring good fortune for the new farming year. The dolly is likely

to represent mother earth, or Eartha, who in mythology would be fertilised

each year by Sky Father to bring forth the new crops of the new season. In

time, she became associated with the Holy Mother of God who brought forth the

incarnation of God himself into our world. Michaelmas

used to be a major feast in England, but is hardly noticed by most people

today. And yet it is a hugely important folk festival, our traditional

harvest festival and the English equivalent of American Thanksgiving. There

are some signs that it is regaining some of its popularity and this is to be

encouraged. Feast of the Guardian Angels (2nd

October)

A guardian angel is an angel that is

assigned to protect and guide a particular person, group, kingdom, or

country. They offer prayers to God on our behalf and can warn us on impeding

danger. Some people claim to have seen them. The concept goes back deep into

our folklore where there was a strong belief in spirits (wights) that

inhabited and protected various places. O angel of God, appointed by divine mercy to be my guardian, enlighten and protect, direct and govern me this day. Amen. St Alfred the Great (26th

October)

We

consider Alfred to be our greatest king and protector of our land and people.

He paved the way for the Anglo Saxon tribes to come together to form England.

He was a great champion of learning and the rule of law. His canonisation was

halted following the Norman invasion, but we consider him to be a true Saint.

Indeed, he should be the Patron Saint of England. Feast of the Eve of All Hallows

or Hallowmas (Halloween) (31st October)

This

marks the beginning of the three day period of Hallowtide. All Hallow’s Eve itself is a day of preparation for the two

principal feasts that follow it. It is a celebration of family, both living

and dead, and a time to light candles to welcome ancestral spirits into our

homes and to say prayers for them. It is also a time for a bit of fun,

carving out Jack’o’Lanterns from Swedes or

Pumpkins, dressing up in ghoulish outfits, trick or treating and playing

party games. All Saints Day (1st

November)

This

is a day of more sober reflection following the merriment of All Hallows Eve.

It is a celebration of our Saints and Martyrs, collectively known as the

‘Communion of Saints’. On this day, we should remember the holy people of our

folk and of what is needed to become a Saint. We should also remember our

martyrs and heroes who have died for our folk and our faith. All Souls Day (2nd

November)

All

Saints is followed by the Feast of All Souls, which celebrates Faithful Departed.

These are all those souls who have not yet been purified and perfected in

heaven. It relates more to one’s own departed family and ancestors, but can

also celebrate the dear departed of our folk as a whole. On this day, we

remember them and pray for them to help them on their journey to become

Saints. It also used to be customary to visit graves on this day and to hold

special meals in which the departed are remembered and commemorated. A

traditional biscuit eaten on this day is the ‘soul cake’, a type of short

cake. I remember these at school. They were eaten with prunes and custard and

we called them ‘grave stones.’ Remembrance Day (11th

November)

They shall grow not old, as we that

are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in

the morning, We will remember them. On

this day we remember and honour those who have died and been injured in wars

protecting our freedom and independence down the years. It is a strange

coincidence that, and for different reasons, the Anglo Saxon term for

November means ‘blood month’ or even ‘sacrifice month’. Christ the All Ruler

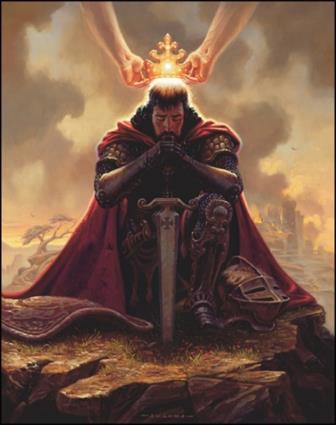

This

is held on the last Sunday before advent and better known as Christ the King.

In Greek Orthodox Churches, He is known as Christos Pantokrator, meaning

Ruler of All. On

this day, we focus on Christ as the Ruler of the World, the Cosmic Christ who

transcends all matter. This is the resurrected and ascended Christ. He is the

Christ that remains with us to this day and with whom we have a personal and

collective relationship. We are reminded that Christ is strong, not weak, and

that our faith is in compassionate strength. Christ

the All Ruler is the ultimate Knight. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||