|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

St George’s

Day

|

|

Every English person has heard of St George, or should

have! He is the patron Saint of our country and yet most Churches only pay scant

attention to him. The Roman Catholic Church, for instance, now honours him

only as a minor Saint, whilst some authorities claim he never existed at all.

The English have always been a bit ambivalent about celebrating St George’s

Day. Although it is gaining in popularity, it is still celebrated less in

England than St Patrick’s Day! This is maybe partly because George is not

seen as an indigenous Anglo Saxon hero – then again St Patrick was not Irish.

It may also be down to England’s Protestant culture which places less

emphasis on Saints, especially when they are steeped in myth and legend. |

||||||||||||

|

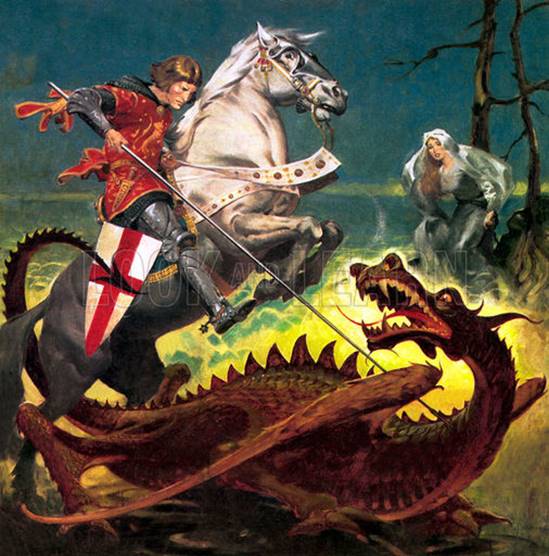

Part of the problem is that, whilst it is generally

accepted that George did exist, very little is known about him. Furthermore,

the story of him slaying a dragon is myth grafted on to the real person. Yet

in the middle ages, his feast day was celebrated with almost as much

enthusiasm as Christmas. He is still greatly honoured in the Orthodox Church,

where his feast day is November 23 rather than April 23 as in the western

Churches. One of the reasons that lead to confusion about St George

is that there are several stories attached to him. Perhaps the best known is

called the ‘Golden Legend’. In this, a dragon lived in a lake near Silena

in Libya. Whole armies had been destroyed trying to kill the monster. It ate

two sheep a day, but when these could not be provided, local maidens were

sacrificed instead. One day, so the story goes, the King’s daughter drew the

unlucky lot and was to be given to the dragon to devour. St George, who was

conveniently passing by, came to her rescue, killing the dragon with a single

blow from his lance. He then delivered a powerful sermon and converted the

locals to Christianity. He also distributed his reward money among the poor

and rode off into the sunset! However, this story is

clearly myth and allegorical in nature. It is also likely to be relatively

late in origin as the earliest accounts of him do not feature the dragon.

There are several of these early accounts. Eusebius of Caesarea, writing in

about 322, provides the earliest hint of an historical account, although he

does not mention George by name. He tells of a

soldier of noble birth who was put to death under the Roman Emperor

Diocletian at Nicomedia on 23 April, 303, but gives no further details.

Another important early text relating to the life of St

George is called the Vienna Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a manuscript that has

had its original text deleted and new material overwritten onto it. Also

written in Greek, this script dates from the fifth century. As with many

texts of this period, it includes material which is clearly of a mythical

rather than factual nature. Nevertheless, it is thought to have been very

influential in the development of the St George story. It claims to be based

on an earlier account written by a servant of George called Pasicrates. This is a common claim in the writings of

early Saints, intended to give weight to their authenticity or perhaps to

give them the illusion of authenticity. In this account, George is again of

Cappadocian origin, but this time living in Palestine. The story runs along

similar lines to the one described above. George visits the pagan ruler, Dadianos, seeking promotion within the Imperial army. Dadianos has banned Christianity and ordered his people

to sacrifice to the Roman Gods. George refuses to do this and gives away his

money and possessions to the poor.

The evil ruler Dadianos, has been described as a tyrant or dragon. This may be an

allegory that grew into the story of St George slaying a dragon. There is, in

fact, a tradition in Greek Orthodox icons to depict St George slaying a man

with sword and shield rather than a dragon. The increasingly unrealistic nature of the stories

associated with George, led in 494, to Pope Gelasius

to conclude the life of St George as being absurd. However, it was decided

that he should remain a Saint and he was grouped with others who are revered

by men, but ‘whose actions are known only to God’. In other words, the Church

accepted the authenticity of George as a genuine martyr, but was not

convinced of the legend attached to him. But the mythical stories attached to

George continued to grow and develop in ever more flamboyant ways,

culminating in the George and the dragon story we know today.

Another influence on the story is thought to be the Emperor

Constantine (272 – 337). Constantine

was the first Christian Emperor and his conversion did much to ensure the

supremacy of the Christian faith over others within the Empire. Constantine

built a Church in the City of Lydda in honour of St

George. Some authors have suggested that this Church included a statue of

Constantine standing on top of a dragon or serpent and holding the banner of

the cross in his right hand. It is suggested, therefore, that the early

followers of St George mixed these two images. The period of Constantine

may also provide a context for the development of the cult of St George.

Constantine, whilst being the first Christian Emperor, carried on practicing

his old pagan religion throughout his life and was not actually baptised until he lay on his death bed. He did, however, issue

the edict of Milan in 313 which granted religious freedom within the western

Empire over which he ruled. Licinius, the Emperor

of the eastern Empire continued to persecute Christians, though, and this led

to a civil war between east and west in 324. Constantine won this war,

marking the beginning of the Christian ascendancy in Europe. The Orthodox Church is clear that George was a real human

being. A typical story current in the Church is similar to that found in the

1964 manuscript, though with some differences. The Orthodox account has

George born into a noble Christian family in Cappadocia rather than Nubia.

Following the death of his father, he was brought up as a soldier and became

a great military leader. In his early life, Dadianos,

the King of Persia, decreed that anyone not worshipping his 'idols' would be

persecuted and tortured. When visiting the port city of Tyre (in modern

Lebanon), George saw the people bowing down to these idols. He reputably went

up to the King and boldly proclaimed the Christian faith. Apparently, this

didn't go down too well with the Persian king, who shoved him into prison and

tortured him mercilessly. In prison, the Lord came to George and told him he

was going to suffer the 'greatest' of martyr’s deaths - not once, not twice,

but three times! He would then be raised up in glory to heaven. During this period of torture and persecution, which lasted

seven years, many people reputably witnessed George's bravery and became

Christians themselves, including the King's wife. After seven years, King Dadianos decided to change strategy. He offered his

daughter to George in marriage if only he would worship his gods. George

pretended to accept this offer, but he called out to the Lord instead and the

idols were destroyed. For this, George was beheaded and declared a Christian

Saint. The Venerable Bede (673 – 735) records St George in his martyrology. He recounts that the Saint was martyred on

April 23 on the orders of Dacian who he describes as a ‘Persian King’. Bede

also recounts a story told to Abbot Adamnan of Iona

by Bishop Arculf who had visited Lydda and been to the shrine of St George there. Here, he

was told a story of how a man had promised to hand over his horse to George

in return for his protection. The man reneged on this promise and so the

Saint made the horse wild and unmanageable thus forcing the man to keep his

promise. Perhaps more importantly, Bishop Arculf

would have seen the statue of Constantine standing over the dragon.

During the middle ages, stories developed that St George

had travelled to Britain as a tribune of the Roman army on the orders of

Diocletian. For instance, he is said to have been a friend of Helena, the

Empress, and it is claimed that he found the ‘True Cross’ on which Christ was

crucified. It is also said that Helena dedicated a Church to George in

Jerusalem close to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Other traditions tell of

St George visiting the tomb of St Joseph of Arimathea, to whom he was

related, in Glastonbury. These, and other, stories reflect the development of

the cult of St George in England which culminated in his becoming our Patron

Saint. The Anglo-Saxon writer Aelfric wrote a commentary on St

George around the year 1000. He describes the Saint as being a ‘rich eoldorman, under the fierce Datianus,

in the shire of Cappadocia’. A monastery was dedicated to St George in

Thetford during the reign of King Canute (1017 – 1035). There was also a

Church of St George in Southwark during the Anglo-Saxon period and one

dedicated to him in Doncaster in 1061. The collegiate Church of St George in

Oxford was dedicated in 1074, just after the Norman invasion. He became the

Patron Saint of England by the end of the fourteenth century and in 1415, the

year of the battle of Agincourt, his feast day was declared to be a major

feast to be observed like Christmas.

The cross of St George was incorporated into the uniform of

English soldiers, possibly during the reign of Richard I. When Richard II

invaded Scotland in 1385, every man was ordered to wear ‘the arms of St

George', both on their front and backs. Any enemy soldiers who also wore such

a cross were put to death. The supposed tomb of St George can still be seen at Lod, south-east of Tel-Aviv; and a convent in Cairo

preserves personal objects which are believed to have belonged to him.

So how has this Middle Eastern character, who had probably never heard of England let alone been

here, become our patron saint? The answer seems to lie in the crusades and

the medieval taste for giving the Christian religion a Germanic ‘heroic’

gloss. The imagery of the dragon is not part of the original story and seems

to have been added later and Christianised to embellish the myth that had

already grown up around George in medieval times. The Orthodox explain this

imagery by saying that the dragon represents the devil and that by 'slaying'

him, George is overcoming evil and representing the victory of the Church. His name, George, could be derived from the words ‘geo’,

suggesting ‘earth’ and ‘orge’, suggesting to ‘till’. In other words, he who tills the earth. He is also known as ‘Green George and in

Islam is called ‘al Khidir’ – the green one. His

festival in the western world is on April 23 and so associated with the

coming of spring and new vegetation. He is killed several times (depending on

which legend you are reading) and rises back to life on all but the last

occasion. Whilst this may not be part of the original story, there does seem

to be a strong association with the dying vegetation God best known to the

English as Ingeld or Ing Freyr. His association with vegetation and name as the

‘Green One’ could also be the origin of the mediaeval custom of the ‘Green

Man’, brought to England from the middle east during the crusades. Heroic warriors fighting dragons is a deep and well

established part of Germanic mythology. The Icelandic epic Volsungasaga tells the story of Sigurd the dragon slayer. The old High German epic Nibelungenlied mirrors this tradition with

the story of Siegfried. For the English, the legend is best known through the

epic tale of Beowulf. Here, the hero defeats the monster Grendel, and his

mother, and wisely rules over his people for many years. In old age, he is

called on to defeat a dragon who has been disturbed

by someone trying to steal the treasure hoard he was guarding. Beowulf is the

only one brave enough to fight the dragon and a heroic battle takes place.

Although our hero defeats the dragon, he is himself mortally wounded and soon

after dies.

This treasure held great symbolic meaning to our ancestors.

The King was chosen as the link between the tribe and the gods. It was said

that he held the tribes' luck' or ‘Maegan’. This was represented by his

treasure, which he held in trust for the tribe as a whole. However, 'luck'

had a deeper meaning than it does now. It referred to the tribe's well-being,

the gods and with nature. It was linked to their collective Wyrd or fate. If

the King was in favour with the gods, all went well with the tribe. They

prospered, had good harvests, did well in battle and

so on. But if the King's luck' diminished, things would go wrong. Harvests

would fail, wars would be lost and the tribe would suffer starvation, disease

and defeat. So what is the significance of the dragon guarding the treasure

hoard and of the heroic fight against it? At the heart of the dragon stories lies our ancestors' understanding of the world, passed

down to us in myths and legends. These myths contain profound wisdom that we

are only just beginning to once again understand. For the dragon does not

simply represent evil, slain by the righteous hero. It represents something

far more profound. Firstly though, we need to understand what our ancestors

understood dragons to be.

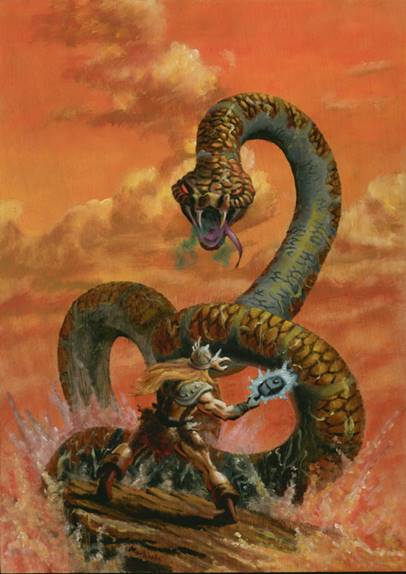

They are in fact a type of snake, the Old English word Wyrm being used for both. Snakes are seen in

northern mythology as a representation of the forces of chaos, negative

change and destruction. The Norse myth of the world serpent Jormungandr demonstrates this view well. At the

end of the current time cycle, or the Ragnarok, he

battles with the gods. He is defeated and slain by Thor, but Thor himself

dies of terrible wounds inflicted in the fight. Interestingly, this reflects

the Beowulf story. The Ragnarok is itself a

mythological representation of part of the time cycle when great changes come

about. The forces of chaos represented by the Giants, the Fenris

Wolf and the World Serpent represent negative change and destruction of the

established order. It is interesting that the early legends of St George

refer to the people that he battles against as ‘Paynims’,

a term that came to be seen in the middle ages as synonymous with Giants.

This does seem to be another indication of how a Middle Eastern legend was

absorbed and adapted into earlier folk lore which must have lain in the

collective memories of the people rather than having died out as is so often

assumed. The concept of a cosmic battle between good and evil, light

and darkness lies at the heart of Indo Euroean

religion and is central to religions such as Zoroastrianism. In this fight

and the myth of St George, then, we have a window into a particular Indo

European and Germanic theology which is an important element of restoring

Germanic or Saxon Christianity.

So the cult of St George is many things. There is a real

man behind the stories and whilst he never set foot in England he has come to

embody English chivalry. Unlike rivals such as St Cuthbert and St Edmund (to

whom we give great honour), George has come to represent the whole of England

and is not a ‘regional’ saint. In many ways his only rival as Patron of

England is King Alfred the Great who we also greatly honour. But George has

something else and this is the mythology that surrounds him and which has

made Church bodies down the ages suspicious of him. This myth,

is something that goes deep into our Anglo Saxon identity and has much to

teach us about the world view of our ancestors. Fighting the dragon above all

else embodies the Indo European idea of good fighting evil to overcome the

forces of chaos and maintain order. As such, St George really is an English

icon; an embodiment of Saxon Christianity we seek to restore. But there is another aspect to George’s slaying of the

dragon which speaks volumes to us in our modern world. In this we see the dragon

representing the greed, degeneracy and anti-English prejudice that has

gripped our nation’s ruling class. The dragon can be seen as a symbol of

multi-culturalism and cultural Marxism which is slowly strangling a once

proud and productive people. St George is the embodiment of our fight back

against all of this and the final victory that we know will be ours. To this end, we pray to George for the preservation and

protection of England. |

||||||||||||||