|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Who Is My

Neighbour?

|

|

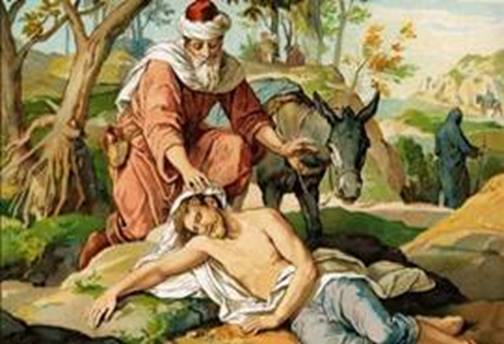

The

story of the Good Samaritan is one of the best known stories of the Bible. It

is also one of the least well understood. Although it is primarily about

mercy and decency, it has been corrupted and co-opted to become a standard

bearer for modern notions of diversity and multi-cultural societies. As

we shall see, this is not the true meaning of the story at all. |

|

When

asked by a Scribe (expert in Jewish law) what he must do to attain eternal

life, Jesus says to him “what is written in the law?” The Scribe replies that

it is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, all your soul and with all your mind” and to “love your neighbour as yourself”.

Jesus tells him that he has answered correctly and if he does this he will

have eternal life. But the scribe goes on to ask Jesus, “who is my

neighbour?” In response, Jesus tells the story of the Good Samaritan. “A

certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, who

stripped him of his clothing, wounded him, and departed, leaving him half

dead. Now by chance a certain priest came down that road. And when he saw

him, he passed by on the other side. Likewise a Levite, when he arrived at

the place, came and looked, and passed by on the other side. A Samaritan then

came upon him and when he saw him, he felt compassion. So he went to him and

bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; and he set him on his own

animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him. On the next day, when he

departed, he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said to

him, ‘Take care of him; and whatever more you spend, when I come again, I

will repay you.’ Which

of these three do you think was neighbour to him who

fell among the thieves?” The scribe replied, “He who showed mercy on him.”

Then Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.” Luke

10:27 Similar

accounts of this parable are included in both Mathew and Mark. But

what is actually meant by the term ‘neighbour’ in this context. Clearly, it

is not referring just to the person we happen to live next door to! The

traditional Hebrew understanding of ‘neighbour’ is set out in Leviticus,

19:17-18: “You

must not hate your brother in your heart. You must surely reprove your fellow citizen

so that you do not incur sin on account of him. You

must not take vengeance or bear a grudge against the children of your people,

but you must love your neighbour as yourself. I

am the LORD.” The

Hebrew word for neighbour is ‘Rea’. According to Strong’s concordance, this means

a ‘friend, companion or a fellow, specifically a fellow Israelite.’ In this

sense it has more in common with the English word ‘Kin’. The Old Testament

was, first and foremost, teaching Israelites how to deal with each other and

not to mix with the alien peoples amongst them. It

does not have the same meaning as the word ‘neighbour’ in English. The modern

English word ‘neighbour’ is derived from the Old English word ‘neahgebur’; ‘neah’ meaning

‘near’ and ‘gebur’ meaning ‘dweller’. It has

therefore always had pretty much the same meaning, namely someone who

physically lives near to you. You might have a good neighbour or a bad

neighbour. They may be your best friend, sworn enemy or you may not know them

at all. They may be part of your kinfolk or not, although for most of our

history they would have been. There is a sense of kinship or

‘neighbourliness’ implied in the term, mainly down to the notion that it is

better to be on good terms with the people you live near to than at

loggerheads with them. However, it is a different concept to the Hebrew ‘Rea’

which is not restricted to people you live close to.

As an aside, the Old English word ‘gebur’ tends

imply someone living off the land (as most people did in those days) or a

farmer and is therefore cognate with the Dutch and Afrikaans word Boere. The

Greek term used in the Scriptures, πλησίον

(plesion), has much the same meaning as the English

word ‘neighbour’ and it is this word that is used in the New Testament to

express the Hebrew meaning of ‘Rea’. So we can see a subtle change that has

resulted from this Greek word being used in the New Testament in place of the

Hebrew word ‘Rea’ which does not actually mean the same thing. Jesus

is not asking who is the better ‘neighbour’ in the sense of who is it better

to live next door to. He is asking who has acted as the better citizen. He is

making the point that somebody who is not of your folk or tribe can act more

compassionately and more civilly to you than somebody who is of your tribe.

He is not seeking to repeal the commandments that God gave to the Israelites,

and indeed all peoples, to remain separate. He is not suggesting that the

Israelite traveller should invite the Samaritan to live in his household and

offer him his daughter’s hand in marriage! This

confusion in terminology is now being deliberately used by some to promote

multi-culturalism and the idea that it makes no difference what race or creed

your ‘neighbour’ (in the sense of the person you live near to) is. A good

neighbour is simply someone who treats you with compassion and kindness.

Similarly, we are to treat our physical neighbour, whoever they may be, in

the same way. In particular, we must be accepting of their difference as all

that counts is how we treat each other. This fits in with the modern concept

of civil society based entirely on ‘values’ rather than kinship as it used

to. However,

this parable is about community. It is about compassion and how we deal with

people in general, what we used to call human decency. Jesus was saying that

we should treat all people with respect and kindness, irrespective of whether

they are part of our folk group or not. He is simply repeating the teaching

that we should treat others as we would want them to treat us – the law of

reciprocity. This is not the same thing as blinding ourselves to the

differences between people or abandoning the divine laws of ‘kind after

kind’. It is an argument for compassion in general, not for mass immigration

and multi-culturalism. This

law of reciprocity is actually quite an old one and common to many religions.

Within Anglicanism, it is known as the ‘Golden Rule’,

or ‘Golden Law’ and was first coined around the early 17th century in Britain

by Anglican theologians and preachers. An act of kindness under the ‘Golden

Rule’ is made because it is the decent thing to do, not with an expectation

of anything to be returned. That said, the law of

reciprocity would imply that somebody should repay an act of kindness even if

this is not expected. This law is summed up in the Old English Rune Poem as a

‘gift for a gift’. So,

the parable of the Good Samaritan is a story of recognising the humanity of

all people and dealing with them fairly and with kindness whoever they are.

It is a story of good practice in relationships between people and between

tribes and ethnic groups. It is not a story about the mixing of peoples or

creating multi-racial and multi-cultural societies. It does not support mass

immigration and miscegenation as some would have us believe. We should

certainly act compassionately to people in need, the refugee and the world’s

poor. The story is saying that we should not turn our backs on people in need

and pretend they and their problems do not exist. But this does not mean we

should invite them into our own lands. There are other, better, ways we can

help. |

||

|

|

||